A Living History: Introduction

- Kally Hanifin

- Jan 11, 2025

- 3 min read

My name is Kally and I love history.

I can, and very often do, waste a whole day wandering around a historical place, daydreaming about who stood in the exact spot where I stand. I spend a lot of time ruminating about the lives of the residents of very old cemeteries. Got a dusty relic of a bygone era? Please allow me to research every facet of its potential historical importance.

When the Richmond Historical Society needed volunteers to work in the archives, it was a very natural choice to sign up. Spending hours picking through cracking, faded, handwritten documents from 200 years ago? Yes, please! When they asked me to start writing a blog for the website, I couldn’t imagine a more fulfilling task.

History is just the stories of people. What we consider “history” only started when we humans started writing it down. It could be the macro view of life that we learned in school, or it could be dialed in to the tiny state where you live, how your street got its name, or who your ancestors from 100 years ago were.

I find it very easy to empathize with people from the past whose lives I learn about through documented history. I am as intrigued by the small-town folk who lived quiet lives as I am by the famous change makers. If they wrote it down, they must have believed that someone, one day, would like to learn about it. And here I am.

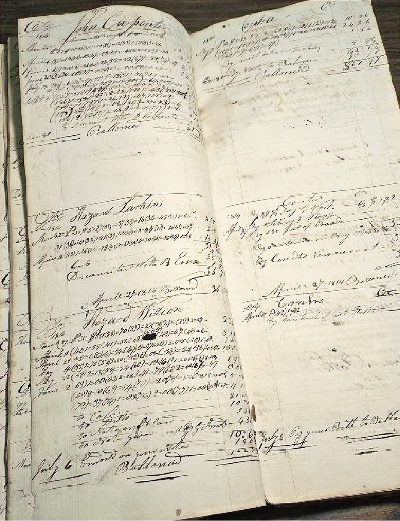

Take, for example, the prolific leather-bound books of mill records, now housed in the archives. The mills represent a time of enormous change in the way people lived their lives when the Industrial Revolution began. Mill workers began living close together in mill villages. They bought the goods they needed rather than living on sprawling farms and growing food for themselves and their livestock. Mill ledgers show the wages of the laborers in those mills, as well as the goods that the mill purchased, and how much income the business brought in. You can see the same names, year after year, and make deductions about who they were.

Sometimes, if there is a trail to follow, you can cross-reference a name to other documents, photos, or items. You can build a snapshot of their daily lives, and even seek out their final resting places. If you’re like me, you can visit them, read the stones, and, for a moment, feel connected through time.

When I began researching the mill ledgers to write this, I pulled several books from the archives. I hadn’t decided on a more specific theme for the article, so I wanted the handwriting to speak to me. I wanted it to tell me how important it was as an archival resource so that I would be better able to tell you.

In the first book I opened, I saw the signature of a very familiar name:

Fred S. Wright, my great-grandfather.

I come from a family of like-minded, historically infatuated people, so I knew that Fred Wright was from Richmond. My father still makes flower boxes for his grave in Wood River Cemetery.

Fred was a local businessman, and when he signed this particular document in 1916, he was only 25 years old. He and his wife Catherine went on to have a large family, including my paternal grandmother. The most exciting part about history, in my opinion, is when you can see your place in it.

For me, this project went from an academic study of the Industrial Revolution to a personal journey to learn about a member of my own family.

So this is your call to action. What historical plaque have you passed by and never made time to stop and read? Who was your street named after? Do you have ancestors in local cemeteries whose stories need telling? A visit to the archives can answer these questions and more.

Enjoyed the read. I'm a docent there

I am interested in learning more about beaver river farms and owners. Who should I talk to that knows about this? And where are the archives?